Homeowners Association (HOA) fees are a fact of life for millions of homeowners. These fees support the shared amenities and services in your community – but as tax season rolls around, many homeowners wonder if their HOA fees are tax deductible. The short answer is generally no, HOA dues are not tax-deductible for your primary residence according to the IRS.

However, there are important exceptions and special cases to understand. In this authoritative guide, we’ll explain what HOA (and condo association) fees cover, when you can deduct them (such as for rental properties or home offices), and other key questions like fee increases, special assessments, and your HOA board’s responsibilities. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of HOA fees and taxes – knowledge that every homeowner in an HOA (whether a first-timer or seasoned resident) should have.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute tax, legal, or financial advice. Always consult a certified tax professional or CPA regarding your specific situation.

What Are HOA Fees and What Do They Cover?

HOA fees (also called condominium association fees or simply “association dues”) are regular payments owners must make to their community’s governing association. When you buy a home or condo in a development with an HOA, membership is mandatory – you automatically agree to pay these fees and abide by community rules. What do HOA fees pay for? In general, they cover the shared expenses of running the community, which can include:

- Maintenance of common areas and facilities: This is usually the largest component. HOA fees pay for upkeep of landscaping, parks, playgrounds, lobbies, hallways, swimming pools, fitness centers, and other shared amenities. For condo buildings, fees also cover building maintenance and repairs (roof, elevators, etc.).

- Community services and utilities: Many associations include services like trash removal, recycling, water/sewer, or security patrols in the dues. If your neighborhood has gate security, street lighting, or pest control, those contracts might come from HOA funds.

- Insurance and administrative costs: HOAs often carry liability insurance for common areas or a master insurance policy for a condo building. A portion of your fee goes toward insurance premiums, as well as management expenses, legal/accounting fees, and admin costs to run the HOA.

- Reserve funds for future projects: A healthy HOA sets aside part of the fee into a reserve fund each month. The reserve is savings for big-ticket projects or unexpected emergencies (like repaving roads or repairing storm damage). This way, the HOA has money on hand and can avoid huge surprise bills to owners. (If reserves are insufficient, the HOA may levy a one-time special assessment, which we’ll discuss later.)

Typical costs: HOA fees vary widely depending on your location, home type, and amenities. Some small single-family communities charge only a few hundred dollars per year, while luxury condos in big cities can run hundreds per month.

In 2024, the national average HOA fee for a single-family home was roughly $250–$300 per month, and condos averaged a bit less. Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all – a homeowner in a suburban neighborhood with minimal common areas might pay $50/month, whereas an urban high-rise condo with a gym, pool, and 24-hour concierge could charge $1000+ monthly. It’s wise to research “HOA fees near me” to gauge what comparable communities charge, but remember that amenities and local costs drive the differences. The key point is that HOA fees fund your community’s collective needs, effectively pooling resources so everyone can enjoy well-maintained facilities.

General Rule: HOA Fees Are Not Tax Deductible for Personal Residences

Now to the big question: Can you deduct HOA fees on your taxes? According to IRS guidelines (as of 2025 and for the foreseeable future), HOA fees are considered a personal living expense, not a property tax or interest, and therefore are not deductible on your federal tax return. This holds true whether you call them HOA fees, condo dues, or common maintenance charges – if the property is your primary residence or a second home for personal use, you cannot deduct those HOA payments.

The IRS explicitly lists homeowners association fees alongside utilities and home repairs as non-deductible items. In other words, paying your monthly HOA dues is treated the same as paying your electric bill or buying lawn tools – it’s part of the cost of homeownership, not a special tax break.

It surprises some people that HOA dues aren’t deductible, especially since certain other home expenses (like mortgage interest and property taxes) often are. But it’s important to understand why. Property taxes go to a government authority and are deductible (within limits) as a tax paid.

Mortgage interest is paid to a lender and deductible as the cost of financing your home. In contrast, HOA fees are paid to a private association for maintenance/services that benefit the community members rather than the general public. The IRS views this as a personal benefit, not a tax-deductible expense. Just as you can’t deduct your homeowner’s insurance or the cost of mowing your own lawn, you typically cannot deduct HOA assessments if the home is for personal use.

What about senior communities (55+)? Some homeowners in age-restricted or retirement communities wonder if their HOA fees get any special tax treatment – for example, if the fees cover services for seniors. Generally, no, there is no special deduction purely because a community is 55+ or geared toward retirees. The HOA fees in an active adult community pay for amenities (clubhouse activities, landscaping, maybe a shuttle bus, etc.) just like any other HOA – these are still considered personal living expenses.

Unless a portion of the fee is explicitly a medical or assisted-living expense (which is rare in a standard 55+ HOA; those are typically separate charges or in a different type of facility), the age or nature of the community does not make HOA dues tax deductible. So, whether you’re 35 or 75, if you’re paying HOA dues on your primary home, the IRS treats them the same way.

Bottom Line: For your personal residence (or vacation home that you don’t rent out), you generally cannot write off HOA fees on your federal taxes. This rule catches many first-time homeowners by surprise, especially if their mortgage lender escrowed HOA payments with the mortgage. Remember, only property taxes and mortgage interest (and some mortgage insurance or energy credits) are deductible from those escrow payments.

If your bank collects HOA dues with your mortgage payment, they do it for budgeting convenience, not because those dues become tax-deductible – they don’t. The IRS allows you to deduct state/local property taxes and qualified mortgage interest that a lender pays on your behalf from escrow, but any HOA fees in escrow are simply passed through to the association and remain nondeductible.

When Are HOA Fees Tax Deductible? (Rentals, Home Offices, and Special Cases)

There are a few important exceptions where HOA fees can have tax benefits. While personal-use homeowners are out of luck, landlords and certain business users of a property may deduct HOA costs. Let’s break down the scenarios:

1. Rental Property – HOA Fees as a Rental Expense

If the home or condo is used as a rental (income-producing property), then the HOA fees are considered an ordinary and necessary operating expense of that rental. In this case, HOA fees are tax deductible against your rental income on Schedule E of your tax return, according to hrblock.com. Effectively, the IRS treats association fees similar to other rental expenses like maintenance, insurance, or property management fees.

- Full-year rentals: If you own a property solely as a rental (you do not use it personally at all during the year), 100% of the HOA fees you pay for that property are deductible. For example, suppose you own a condo that you rent out to a tenant year-round, and the HOA dues are $300/month. You can deduct the entire $3,600 paid in HOA fees for the year as an expense against your rental income.

- Part-year or mixed-use rentals: If the property is partly used by you (or vacant) and partly rented, then you may deduct a proportional amount of the HOA fees. For instance, imagine you have a vacation condo that you personally occupy for 3 months and rent to others for 9 months of the year. In that case, roughly 75% of your annual HOA fees would be deductible (since 9 out of 12 months the home was producing rental income). The remaining 25% of HOA fees (for the personal-use period) is not deductible. You’d prorate similarly if you rent a room in your home or only rent out your property on weekends, etc. – only the portion of time (or space) used for rental/business counts.

It’s worth noting that even for rental properties, not every HOA-related charge is immediately deductible. If the HOA imposes a special assessment for a capital improvement (say, a one-time $5,000 fee to build a new clubhouse or replace all the roofs), that is not deductible as an expense in the year paid, because it’s improving the property’s value. Instead, for a rental owner, that kind of assessment is treated like a capital expenditure – you add it to your property’s basis or depreciate it over time. (More on special assessments below.) Regular HOA dues that go toward maintenance or operations are deductible in the year paid for rentals.

In summary, the IRS explicitly allows HOA fees as a deductible expense for rental property owners. If you’re a landlord, be sure to include those fees on your Schedule E. And conversely, if you’re a homeowner who tried renting out your place for a while, remember you can only deduct the fees for the period it was rented or available for rent – not the months you lived there yourself.

2. Home Office – Partial HOA Fee Deduction

Do you run a business from your home or have a qualified home office? If so, a portion of your HOA fees might be deductible as a business expense. Under the home office deduction rules, self-employed individuals (or remote workers with businesses) can deduct a percentage of many household expenses proportional to the space used for the office. This typically includes parts of rent, utilities, and maintenance – and HOA fees can be included as well.

For example, suppose you’re self-employed and you use 15% of your home’s square footage as your dedicated office for work. If your HOA dues are $200 per month, that’s $2,400/year; you could potentially deduct 15% of that amount (about $360) as a home office expense. The logic is that the HOA fee is part of the cost of housing, and your home office makes up 15% of that housing cost. The IRS confirms that if you qualify for a home office deduction, you may include association fees in the calculation, allocated by the business-use percentage.

Keep in mind, home office deductions have specific requirements (the space must be used regularly and exclusively for business, etc.). If you meet those tests, you would claim the HOA fee portion on Form 8829 or Schedule C with your other home office expenses. Note that if you’re a W-2 employee working from home, you unfortunately cannot deduct home office expenses on your federal return due to recent tax law changes – so this HOA fee break mainly helps self-employed folks or independent contractors. Always consult IRS Publication 587 or a tax advisor to navigate home office calculations, as they can be tricky. But the key point here is: an HOA fee isn’t deductible for personal use, but if part of your home is used for a legitimate business purpose, part of the fee becomes a business expense.

3. HOA Fees for 55+ or Retirement Communities

As mentioned, simply living in a 55+ community does not by itself make your HOA fees deductible. However, one scenario to be aware of: if your community or development provides specific care services and charges them via HOA or monthly fees, part of those fees might qualify as a medical expense deduction. This typically applies in continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) or assisted living facilities rather than standard HOAs.

In most age-restricted HOAs, the fees are for maintenance and amenities, not health or nursing services, so no portion is medical. Thus, the HOA dues remain nondeductible (unless the retiree meets one of the other criteria like renting out the home or having a home office). Always differentiate between an HOA fee and other fees (like an entrance fee or care fee) in senior living arrangements – only the latter might have tax implications (and even then, subject to medical deduction limits). For the typical 55+ homeowner paying monthly HOA dues for clubhouse, lawn care, etc., those payments are personal expenses.

4. Special Assessments – Deductible or Not?

Now let’s talk about special assessments, since they’re a common source of confusion. A special assessment is usually a one-time (or short-term) extra fee charged by the HOA on top of regular dues, often to fund a major project or emergency repair. For example, if a condo association needs to replace all elevators or repair extensive storm damage and doesn’t have enough reserves, it might levy a special assessment on each owner to cover the cost. These can range from a few hundred dollars to tens of thousands, depending on the issue. Naturally, homeowners ask: can I deduct a special assessment on my taxes?

- Primary residence: In general, no, a special assessment on your personal home is not tax-deductible – just like regular HOA dues are not. It doesn’t matter that it’s a big, mandatory expense; the IRS still sees it as part of maintaining your private property. There is a narrow exception: if the assessment is related to casualty losses or deductible taxes (for instance, a government special tax assessment for local improvements could be deductible in some cases rocketmortgage.com, or a portion of an HOA assessment that was purely for casualty repairs might be claimable as part of a casualty loss deduction). But those cases are uncommon. Generally, if your HOA hits each homeowner for $5,000 to fix the roof, you cannot write that $5,000 off on your Schedule A. It’s analogous to paying for a new roof yourself – no deduction (though you do add it to your home’s cost basis).

- Rental property: If the special assessment was for maintenance or repairs, a landlord can likely deduct it as a rental expense (since it’s effectively just a larger-than-usual upkeep cost). If it was for a capital improvement, as noted, it isn’t immediately deductible but you add it to the asset’s depreciable basis. For example, say your HOA charges a one-time $10,000 per owner to install a new community HVAC system. If you rent out your unit, you wouldn’t deduct $10k outright that year; instead, you would treat it as an improvement and depreciate it (or increase your basis for when you sell). On the other hand, if the HOA assessment was $500 to cover an unbudgeted repainting of the clubhouse (a repair), that could be deducted by rental owners in that year. The H&R Block Tax Institute explains that HOA fees covering improvements are not deductible as expenses, but rental owners may recover the cost via depreciation.

One more nuance: while you can’t deduct a special assessment on a personal home, it may benefit you later. If the assessment went toward a capital improvement that adds value or extends the life of your property, you can usually add that cost to your home’s tax basis. A higher basis will reduce your taxable capital gain when you eventually sell the home (potentially saving you taxes then). For instance, if your condo HOA assessed you $8,000 for a new roof, you’d record that $8,000 as an increase in your condo’s basis. Years later, if you sell at a profit above the usual exclusion, that higher basis means a smaller gain. This isn’t an immediate deduction, but it’s a tax consideration to keep in mind – especially for improvements in rapidly appreciating markets.

Note: Always keep documentation of any special assessments (what they were for, amount paid, and whether it was for repair vs. improvement). If you convert your home to a rental or sell it, those records become important for tax reporting.

5. Are HOA Fees Reported on Any Tax Forms?

A common point of confusion for homeowners is whether HOA fees show up on any official tax documents — like the Form 1098 that mortgage lenders issue each year.

Form 1098, also known as the Mortgage Interest Statement, reports how much mortgage interest (and sometimes property taxes) you paid in a given year — both of which are potentially deductible. But here’s the key distinction: HOA fees do not appear on Form 1098, even if you pay them through your mortgage servicer. They’re not considered interest or taxes, and they’re not paid to a lender or government agency. Instead, they’re paid to a private homeowners or condo association — and the IRS classifies them as personal living expenses, which are not deductible for your primary residence.

Bottom line: If you’re looking for a tax form related to your HOA dues — there isn’t one. If you're a landlord and plan to deduct HOA fees as rental expenses, or if a portion of your home qualifies for business use (like a home office), you’ll need to keep your own records and report those amounts on your Schedule E or Schedule C. For everyone else, HOA fees won’t show up on your tax forms — and shouldn’t be added to your deductions unless you meet one of those specific exceptions.

Can HOA Fees Increase, and By How Much?

Yes, HOA fees can increase over time – and in fact, it’s normal to see periodic increases. Just like the cost of living, the cost of maintaining a community tends to rise due to inflation, aging infrastructure, and changing needs. If you’ve been in an HOA for a few years, you might have noticed your dues creeping up annually. Let’s explore how much they can increase and who decides:

- HOA Board and Budget: Typically, the HOA board of directors sets the annual budget for the association, and from that budget derives the needed assessment (fee) per homeowner. The board has a fiduciary duty to budget appropriately for maintenance, insurance, reserves, etc. If costs go up (think landscaping contracts, utility bills, insurance premiums, contractor wages), the board may need to raise the regular dues to keep the budget balanced. Many HOAs include a small increase each year (for example, 3-5%) to keep up with inflation and avoid falling behind. It’s not arbitrary – it’s usually based on projected expenses and long-term reserve funding plans.

- Governing documents limits: Most HOAs have provisions in their governing documents (CC&Rs or bylaws) that address fee increases. Some documents set a maximum percentage increase the board can impose without a full membership vote. For instance, an HOA’s rules might say the board can raise dues up to 10% per year on its own authority, but anything beyond that requires approval of a majority of homeowners. This is to protect owners from drastic jumps and ensure transparency. Always check your HOA’s bylaws: they often outline the process for raising assessments.

- State laws: In addition to internal rules, state laws may cap or regulate HOA fee increases. For example, Arizona law specifies that an HOA cannot increase fees by more than 20% per year without a majority vote of the members (cedarmanagementgroup.com). Other states have similar statutes or require certain notices before a large increase. However, many states do not impose specific caps, leaving it to the HOA’s own rules. The common theme is that large increases should involve homeowner input, whereas modest increases can be decided by the board as part of routine budgeting.

- How much is typical? It varies, but a 3% to 5% annual increase is relatively common for HOAs in line with inflation. Some years may see no increase if costs are stable, while other years might see a bigger jump if the HOA needs to build up the reserve fund or face a major insurance premium hike. Importantly, HOAs prefer to raise dues gradually rather than hold dues flat for many years and then hit owners with a massive increase or special assessment later. A study of HOA trends found that total HOA fee collections nationwide rose over 30% in a decade, reflecting how associations have adjusted fees upwards as needed.

- Special assessments vs. dues increases: Note the difference: a fee increase means your recurring monthly/annual dues go up (permanently, until changed again), whereas a special assessment is typically a one-time charge. HOAs might choose one route or both to meet financial needs. For example, they might implement a 5% dues increase and levy a one-time assessment if reserves are underfunded. Regular fee hikes are meant to cover ongoing operations and future planning; special assessments address shortfalls or big projects.

As a homeowner, you might wonder what you can do about rising HOA fees. It’s wise to attend budget meetings or annual meetings where the board discusses finances. HOAs should be able to explain why an increase is necessary – whether it’s due to higher landscaping contracts, a new security service, bolstering the reserve fund, etc. In a well-run HOA, increases are not money grabs but reflections of genuine cost increases or prudent financial planning. If you feel increases are too high or the budget has fat to trim, get involved: join the finance committee or board, or at least vote on board elections for members who prioritize efficient management. Remember that unrealistically low fees can backfire (leading to deferred maintenance and big special assessments later), so a moderate increase can actually protect you from unpleasant surprises.

Special Assessments: Can You Refuse to Pay, or What If You Can’t Afford It?

Few words strike fear in a homeowner’s heart like “special assessment.” These are extra charges that HOAs sometimes levy on all owners, usually to cover a major expense that wasn’t fully funded. Common triggers include extensive repairs (roof replacements, structural fixes), emergency expenditures (storm or flood damage not covered by insurance), or big capital improvements (like adding a new amenity). Special assessments can be costly – in some extreme cases tens of thousands of dollars per unit – so what happens if you simply can’t afford it or don’t want to pay?

Firstly, can an owner opt-out or reject a special assessment? In almost all cases, no – if the special assessment was properly approved by the HOA (per its governing rules), all owners are obligated to pay it (nolo.com). When you purchased your property, you agreed to abide by the HOA’s decisions, including financial assessments. Even if you never use the new tennis courts that are being resurfaced, if they’re a common element, you have to chip in your share. The only time you might legally resist paying is if the HOA failed to follow required procedures in levying the assessment. For example, if your bylaws say “any special assessment over $X requires a membership vote” and the board tried to impose one unilaterally, you could challenge its validity. But assuming the HOA acted within its authority (held the proper vote or followed state law), you are contractually bound to pay. In short, you cannot individually “reject” a special assessment just because it’s burdensome or you disagree with the project.

Consequences of nonpayment: If you ignore or refuse to pay a valid special assessment, the HOA has several remedies – none of them pleasant for the homeowner. Typically, the HOA can charge late fees and interest on the unpaid amount, just like overdue regular dues.

Many governing documents allow the HOA to suspend your privileges (e.g. barring you from using the pool, clubhouse, or parking facilities) until you’re caught up. More seriously, the HOA can usually place a lien on your property for the unpaid assessments. This lien can accrue additional legal fees and, if left unresolved, can lead to foreclosure on your home by the HOA in certain jurisdictions. It’s a power HOAs don’t wield lightly, but it exists to ensure everyone pays their fair share. Nolo’s legal guidance confirms that as long as the HOA is within its rights, a homeowner’s nonpayment can result in a lien and potentially foreclosure, after due notices. The takeaway: refusing to pay is extremely risky – you could end up losing your home or paying a lot more in the end (with collections and attorney fees on top of the assessment).

If you genuinely cannot afford the special assessment, the best course of action is to communicate with your HOA immediately and seek a solution. HOAs often understand that a large sudden bill can strain owners’ finances. In many cases, the board may offer a payment plan for the special assessment. For instance, if it’s a $5,000 per unit assessment, the HOA might allow owners to pay it over 6 or 12 months, or even longer, rather than all at once. This can make it more manageable to budget. Some HOAs also consider loans: the HOA might borrow money as an entity to cover the project, then collect the assessment from owners over several years to pay back the loan (this effectively spreads the cost out, albeit with interest).

There may be an option to use a home equity loan or refinance by the homeowner to cover the cost, which could be worth exploring if you have equity in your property. The worst thing to do is suffer in silence or ignore the bills – instead, owners should reach out to the board/management, explain their hardship, and ask about installment plans or hardship programs. Many HOAs would rather work out a schedule than proceed with liens and legal battles.

Challenging a special assessment: If you believe the assessment is unwarranted or improperly executed, you can technically challenge it legally, but be cautious. As one expert notes, if the assessment is found reasonable and allowed by the HOA’s documents, you could end up paying even more in legal fees by fighting it in court. Before going down that road, review the HOA’s bylaws (with a lawyer if needed) to see if all steps were followed. Sometimes, homeowners successfully petition the board to reconsider or reduce an assessment if they find alternative solutions or point out budgeting errors – this would be a political/negotiation approach before it gets adversarial. If many owners truly cannot afford it, that collective pressure might cause the board to seek a bank loan or other financing method instead of lump-sum payments from owners. But remember, a necessary repair will have to be paid one way or another – by owners now, or by owners later with interest (via a loan), or through higher dues.

Real-world perspective: Special assessments, while infrequent, do happen – and sometimes in eye-popping amounts. For example, after years of deferred maintenance, a high-rise condo in Miami Beach recently hit owners with a $30 million special assessment, averaging about $160,000 per unit. Many residents were retirees on fixed incomes, facing an enormous financial challenge. Situations like this underscore why HOAs raise regular fees periodically and maintain reserves: to avoid such devastating bills. But if you ever face a special assessment, know your rights and options.

You must pay if it’s valid, but you can work with the HOA on how to pay. Some HOAs allow multi-year payoff schedules for large assessments, and it’s wise to attend meetings leading up to the assessment to stay informed or suggest alternatives (like cheaper repair methods or using reserve funds). If selling the property is an option, note that legally, the current owner is usually on the hook for any assessment levied during their ownership (even if you sell, you might have to pay it at closing, or discount your sale price accordingly). So there’s little escape except addressing it head on.

In summary: You generally cannot escape a special assessment in an HOA if it’s properly levied. If you can’t afford it, communicate and seek a payment plan. Don’t just not pay – that route leads to worse financial and legal outcomes. And for peace of mind, it’s always good to keep an emergency fund for these situations if you live in a condo or HOA, because while rare, they can and do occur.

HOA Board Responsibilities During Tax Season (Notifications and Reports)

What role does your HOA’s board or management have when it comes to tax implications for homeowners? In general, HOA boards are not responsible for providing individual tax documents to homeowners, but they should practice good communication about fees and any changes that might affect owners’ finances. Here are some points regarding HOA board responsibilities:

- Annual statements or invoices: Many HOAs provide owners with a year-end statement or payment summary (especially if requested) showing how much in dues and assessments was paid for the year. This can be useful for owners who are deducting those fees for a rental property or home office portion. While it’s not an IRS form, it’s a simple record. Boards aren’t required by law to send out payment summaries, but doing so is a helpful service.

- No 1098 or tax form issuance: As covered, HOAs do not send out tax documents to owners for dues. So the board doesn’t have an obligation like a mortgage company does (no Form 1098 mortgage interest statement, since interest isn’t involved). However, HOA boards do have to handle the association’s own taxes – filing the HOA’s return (often a Form 1120-H) and issuing any required 1099s to vendors or contractors the HOA paid. These are internal duties and don’t directly involve homeowners’ personal returns.

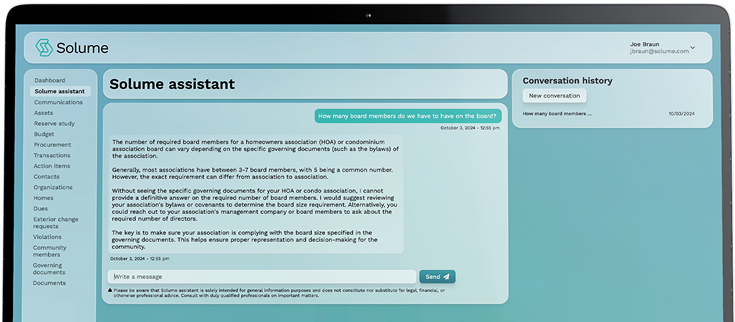

- Educating or reminding homeowners: Some HOA newsletters or communications around tax time may include friendly reminders about what is or isn’t tax deductible. For instance, an HOA might send a January bulletin noting, “HOA dues for 2025 remain $300/month. Please note that HOA dues are generally not deductible on personal tax returns – consult your accountant if you rent out your home or have a home office for possible exceptions.” This isn’t required, but it can preempt confusion. It builds trust when the board shares such information, showing they’re aware owners might be curious (especially new homeowners who might mistakenly try to deduct dues).

- Special assessments notices: If a special assessment was paid during the year, a diligent board might inform owners how to treat it for tax purposes. For example, if an assessment was for a new capital improvement, the board could relay advice (from the HOA’s CPA) that “this is not deductible, but keep this letter for your records as it may adjust your home’s basis.” They have to be careful not to give formal tax advice, but factual statements or guidance to consult a tax professional are appropriate. The board should definitely provide documentation of any special assessment (amount, purpose, date) which owners can use when handling their taxes or when selling the property.

- Timing of dues and increases: Boards should also notify homeowners of any dues increases or upcoming special charges well in advance – not strictly a tax matter, but important for owners’ budget planning. For instance, if dues will go up next year, owners might adjust their tax withholding or quarterly estimates if they have rental income (since a higher expense will reduce taxable rental profit).

- Transparency and records: From a broader perspective, HOA board members have a responsibility to maintain transparent financial records and make them available to homeowners (upon request or at annual meetings). This allows owners (and their accountants) to see where money is going. While not directly about “tax season,” good record-keeping means if an owner gets audited, the HOA can readily verify how much was paid in dues, or what an assessment was for, etc. That cooperation can be crucial if, say, an owner deducted HOA fees for a rental and the IRS asks for proof of the expense.

In essence, your HOA board’s job is to manage the HOA’s finances properly, not to manage your personal taxes. They need to ensure the HOA itself complies with tax filings (which they typically do with the help of a CPA). They aren’t obligated to send each homeowner any tax forms regarding dues. However, a competent and owner-friendly board will communicate changes in dues and provide information that helps homeowners understand the financial and potential tax impact. During tax season, some HOAs send reminders of things like “if you need a statement of dues paid for your records, contact the office.” They might also caution owners: “We cannot advise on your personal taxes, so please consult a professional regarding deductible expenses (e.g., if you rent out your unit or use part of it for a business).” This kind of communication builds trust and reduces misunderstandings.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that HOA board members are usually volunteers (fellow homeowners) and not tax experts. Expect them to know the basics (like HOA fees aren’t federally deductible for personal homes) but don’t expect in-depth tax planning advice. Their responsibility is to run the HOA in a fiscally sound manner and notify homeowners of fees and any changes clearly. Any tax benefits you might get (as a landlord or home business owner) are really up to you and your tax preparer to manage – though certainly you can ask the board for documentation or clarification of what fees were for. Good boards will provide that help readily.

Key Takeaways on HOA Fees and Taxes

Homeowners in HOA communities should approach their fees with a clear understanding of both their purpose and their tax treatment. To recap the critical points:

- HOA fees fund your community’s maintenance, amenities, and reserves. They are an investment in your neighborhood’s upkeep and can protect your property value by keeping common areas in good shape.

- For your primary home, HOA fees are generally not tax deductible. The IRS considers them personal upkeep costs, much like utilities or repairs, and specifically disallows deducting HOA/condo dues. Don’t count on a write-off for those monthly payments (and don’t let anyone incorrectly claim them on a personal Schedule A).

- Exceptions exist if the property is used for business or income:

- Rental properties: HOA dues can be deducted as a rental expense, reducing your taxable rental income.

- Home office/business use: A proportional share of HOA fees can be deducted if you qualify for a home office deduction.

- Improvement assessments: While not immediately deductible, they can increase your basis (potentially reducing future capital gains tax).

- Special assessments – these can be painful, but if you’re a homeowner using the home personally, they won’t give you a tax break in the year paid. If you’re a landlord, they follow the repair vs. improvement rule for deductions. Always keep records; even nondeductible assessments might matter when you sell (for basis) or if you later rent out the home.

- HOA fees can and do increase over time. Expect modest annual increases as normal. Huge jumps typically require member approval or come in the form of special assessments for unexpected needs. Staying involved in your HOA’s budgeting process can give you a voice and foresight into these changes.

- If faced with a special assessment you struggle to afford, don’t ignore it. Work with your HOA on a payment plan, and recognize that legally you must pay if properly levied (or risk liens and worse). Consider it part of the responsibility you assumed by buying into an HOA community.

- HOA boards should communicate clearly about fees. While they won’t give you tax forms for your dues, good boards will let you know about changes, provide documentation if asked, and remind owners of general information (like “dues aren’t deductible” or “consult a tax professional for your rental”). Ultimately, it’s on each homeowner to understand how their HOA payments fit into their personal financial picture.

Living in an HOA can offer wonderful benefits – shared pools, kept-up landscapes, a cohesive neighborhood aesthetic – but it also means shared costs. Approach your HOA fees with eyes open: budget for them, anticipate they may rise, and don’t bank on tax deductions unless you’re in one of the exception categories. If you’re ever unsure, refer back to this guide or seek advice from a qualified tax advisor familiar with real estate. By understanding the rules, you can avoid costly mistakes (like mistakenly trying to deduct non-deductible fees) and you can better appreciate what your HOA is doing for you.

In the end, HOA fees are about preserving your community’s value and enjoyment. While Uncle Sam might not give you a break for paying them, the return on investment comes in the form of a well-maintained place to live – which, though not a line item on a tax form, is certainly valuable for your quality of life and your property’s long-term worth. Trust, clarity, and proactive management – from both homeowners and HOA boards – will ensure that the financial side of community living remains as stress-free and fair as possible.